The earth beneath our major cities is heating up, morphing in ways that could damage buildings, bridges, and transport systems.

Just ask any passenger sweltering on the London Underground or New York City subway, and they'll perspire telling you about how underground transport systems are spewing heat.

As that heat diffuses into the ground, it's raising ground temperatures, which new research shows has shifted soils underneath one US city ever so slightly – but more than most buildings are built to withstand.

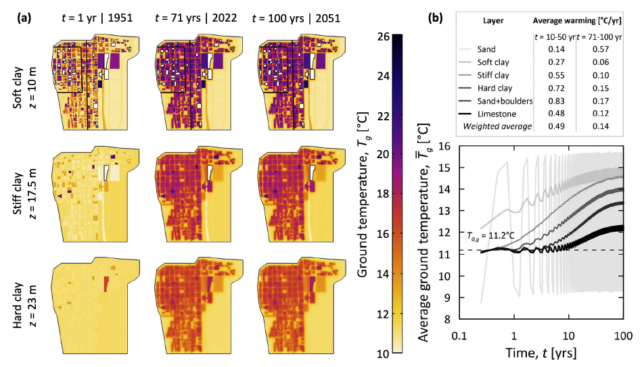

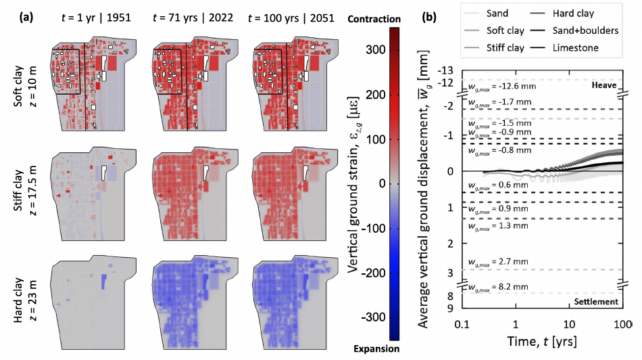

Using the Chicago Loop district as a case study, and three years of data from a network of wireless temperature sensors, civil engineer Alessandro Rotta Loria of Northwestern University in Illinois built a 3D computer model to simulate how rising temperatures have impacted the subsurface environment.

His simulations span a century, from 1951 (the year Chicago completed its subway tunnels) to 2051, and reveal "a silent yet potentially problematic impact of subsurface urban heat islands on the performance of civil structures and infrastructures," Rotta Loria writes in his peer-reviewed paper.

Only recently we learned how New York City could be sinking under the weight of its skyscrapers. Add heat to the mix, and the ground beneath cities can slowly shift, settle, and subside as soils dry out and compact.

Aside from bustling subway tunnels, that heat comes from underground pipelines and electrical cables which crisscross our cities; the ground is studded with the footings of buildings and parking garages that also leak heat.

While all built environments absorb heat from the Sun, fine-grained clay sediments like those below Chicago are particularly prone to shrinking or swelling with heat and water.

Buildings are unlikely to collapse because of slow-moving, heat-related deformations, Rotta Loria says. But subtle subsurface changes of only a few millimeters can strain or mobilize foundations and affect the durability or performance of construction materials over time.

"The ground [in Chicago] is deforming as a result of temperature variations, and no existing civil structure or infrastructure is designed to withstand these variations," explains Rotta Loria who found Chicago's ground temperatures are currently warming at around 0.14 °C per year.

"Although this phenomenon is not dangerous for people's safety necessarily, it will affect the normal day-to-day operations of foundation systems and civil infrastructure at large."

Scientists have known about underground climate change (or subsurface heat islands) for a few decades, recording hotspots in soils and groundwater beneath cities such as Amsterdam, Istanbul, Nanjing, and Berlin.

In Rotta Loria's study, he found larger ground temperature variations in the northern, more densely built part of Chicago's Loop district compared to its sparser, southern end.

Averaged across the whole district, temperatures within distinct soil layers varied by about 1-5 °C (1.8-9 °F). Depending on the soil type, warmer temperatures caused displacements of 8-12 millimeters under various buildings, the modeling found.

While a few millimeters might sound small, and buildings are designed to tolerate some flex, older buildings and other infrastructure were not built to withstand temperature variations seen today, Rotta Loria says.

"It's very likely that underground climate change has already caused cracks and excessive foundation settlements that we didn't associate with this phenomenon because we weren't aware of it," he says.

While cutting emissions to reduce global temperatures would surely ease the strain, some cities are experimenting with using waste heat from transport systems like the Paris Metro to heat apartment blocks and hot water systems.

Called heat recycling, scientists say it's a feasible idea that might become increasingly necessary as the world warms and our cities expand.

"Ongoing underground climate change should be mitigated to avoid unwanted impacts on civil structures and infrastructures in the future," Rotta Loria concludes in the paper.

The study has been published in Communications Engineering.